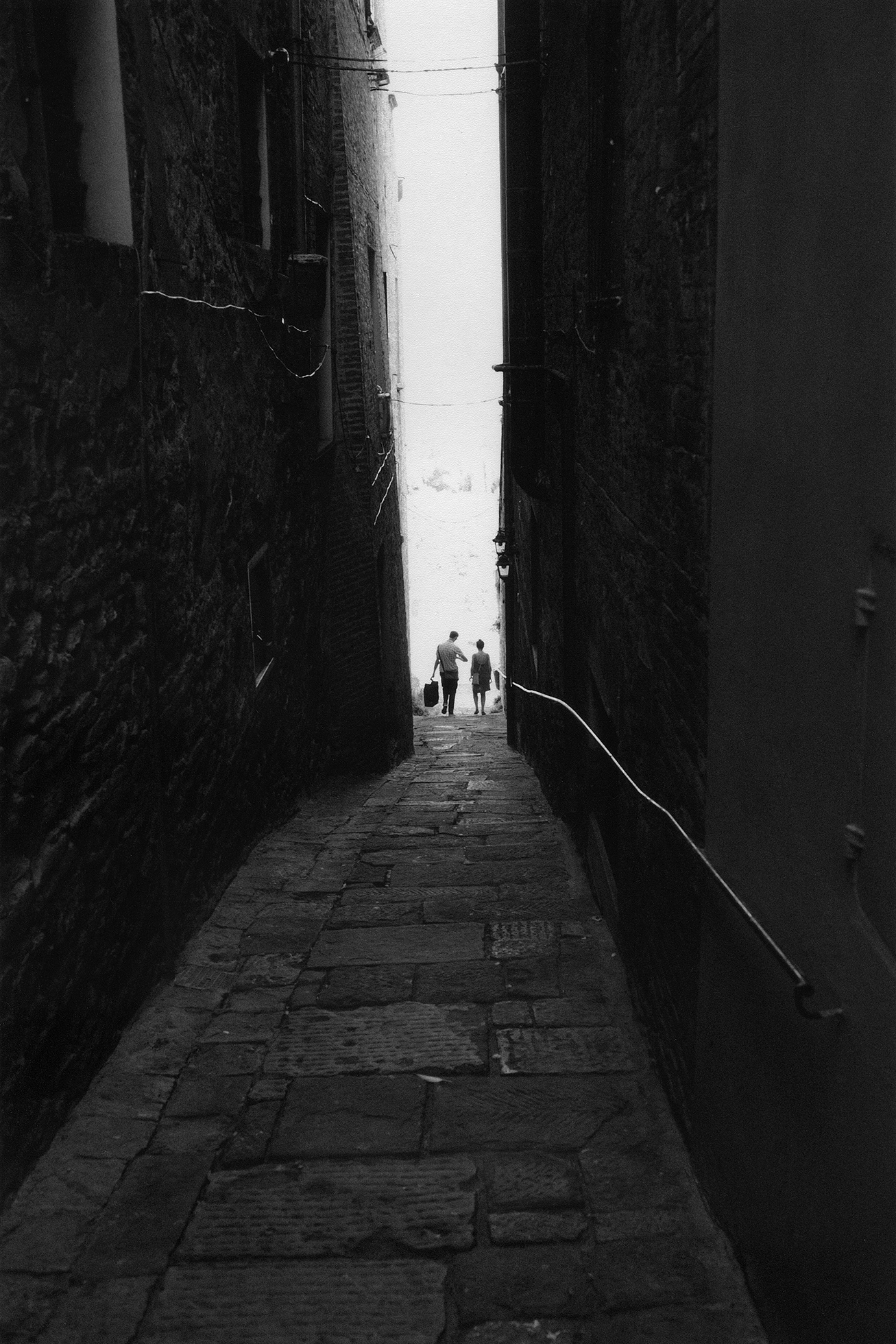

He arrives in London from India in 1991. His Tamil ancestors were converted to Christianity by British missionaries, and he grew up singing English worship songs in church. He got on the plane without his guitar because he couldn’t afford the extra bag. He is wearing a sweater vest and acid-washed jeans, and his hair reaches past his shoulders. There are lots of Indians at Heathrow Airport, but he is the darkest, his accent the thickest. Even in India, if he travels beyond Tamil country in the south, they tease him about his skin. When the border agent stamps his passport, he says a prayer. It must be a mistake; or a miracle. They are letting him in. They are letting him drag his suitcase over cobblestone and pavement to the church he has come to join, the church that is not quite a cult. When he arrives, he is given papers to sign: I will submit to the leadership in all matters, for they are God’s voice. I will submit my money, my body, my mind. I will go where they tell me to go. I will go, and trust God. He signs his name once, twice, a third time. Then there is a dorm with a dozen bunk beds and eleven other men like him, young and lean, and there are jobs to do: dishes to wash and potatoes to peel and tar-covered floors to scrub until his jeans turn black at the knee, because before this building was a church, it was a factory. He wonders if his English is failing him because the words don’t add up when the leaders talk about saving souls before the end of days, when the earth will be engulfed in darkness. Soon, soon, the end is coming, they say. God’s prophets are among us, they say; we must be the life raft, the city on a hill. A day passes quick and another one slow, and the night before Easter they all sit under the leaky roof in the light of fifteen candles. One by one, as the story of Christ’s betrayal and death is told, the candles are blown out. The service is called Tenebrae. It means shadows, darkness, someone whispers to him. He wonders where this name came from, if the Catholics or the Baptists or the Pentecostals invented it; if this church that is free of denominations can draw what it wants from other churches the way it has drawn him from India. Now he’s here, and there had better be something holy in this darkness. So he puts his hands up and opens his eyes as wide as he can and says he has a message from God. Slowly everyone turns. They see a skinny kid who is not quite a man speaking words that are hard to unravel because of his accent. But a guitarist adds in a few strums, and there is something just right about the sour notes, something just right about his trembling prophecy. And he thinks, I can stay. I can make this factory my cathedral. He is eighteen.

Independent, Reader-Supported Publishing

©

Fiction

Believers

Free Trial Issue

Are you ready for a closer look at The Sun?

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue

Also In This Issue

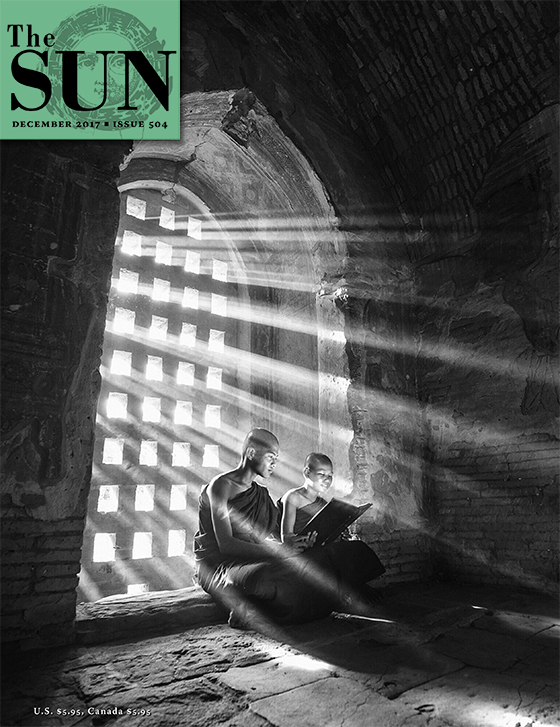

December 2017

close